Your basket is empty

Already have an account? Log in to check out faster.

Already have an account? Log in to check out faster.

When I was a young teen I had a love for extreme sports. I often found myself daydreaming about all of the possible skate tricks I could perform on different obstacles I passed while being toted around town in the back of our family’s minivan, as many youngsters do. Today, as I drive through suburbs, cities and the country alike, I find myself having similar daydreams, except now they’re about grass and cows. Everywhere I go I see future beef and milk potential.

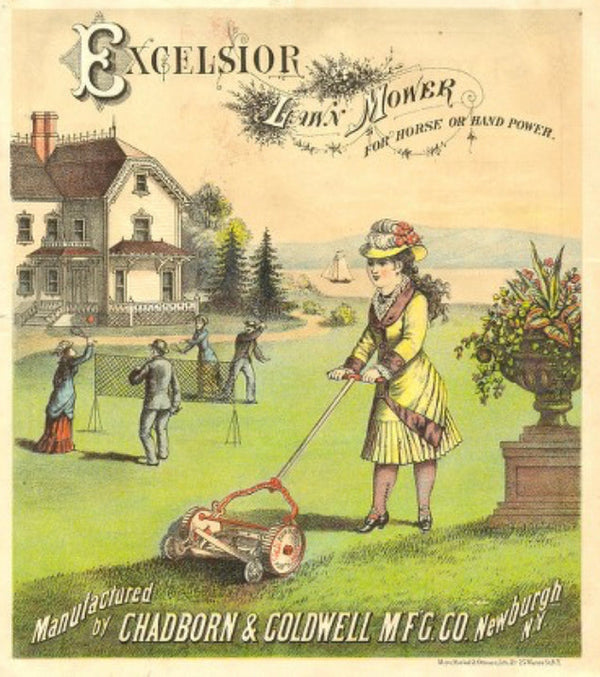

It’s undoubtedly a very childlike fantasy of mine, but I can’t help but notice all the underutilized grass that envelops our world. Every time a lawn mower blade hits the earth I wonder, “What would it be like if it were the mouth of a Jersey cow instead?” I'm well aware of the impractical implications of this inquiry, but perhaps our love for perfect lines has led us to forget that our lawns are food.

Grass is an abundant yet precious resource, and for a long time the world had agreed with this. Our repurpose of it as decor and display has often led us to believe that it is just that; ornamental, instead of a crucial player in our food supply. Grass seems to give and give, yet takes nothing. It is one of the greatest healers of the land and the animals who feed upon it. It’s amazing what good grass management does to a farm ecosystem.

On our farm, cattle grazing is perhaps the most essential aspect to the viability of our operation. Our cattle had been on hay (dried and stored grass) all winter and early spring. Since late March they've been carefully watching the grass grow (a good source of cow-entertainment) as little green shoots began to dot the farm and grow into what are now 6-10” tall blades of dark green nutrition, which they are now all feasting upon fully.

Grazing animals in the early spring sets the tone for grass production for the entire growing season. You can potentially ruin your year if you begin grazing too early and then encounter dry weather in the summer. In a typical year in our area, 60% of all the forage production happens between now and mid-June. Through July and August we have to hold that spring growth over as the heat of midsummer comes and the grass grows and recovers less. Sometimes, if dry enough, it won’t grow at all for weeks on end.

On the other hand, if we wait too long to graze, the forage goes to seed. At times this is helpful for reseeding the pasture, but it means that the grass plants have gone from producing sugar, protein, and soluble fiber– cow rocket fuel– to mainly starch and insoluble fiber. Cattle can certainly survive off of starch and insoluble fiber, but we will not achieve the bodacious animals and large weight gains we strive for off of this type of dead feed.

Once grass goes to seed, it shortly reaches what’s referred to as senescence, the last phase of plant growth in which it stops growing altogether. This means we’re no longer sequestering carbon with that plant. It also means that the water and sunlight on our farm is not being converted into meat and milk; it's simply hitting a solar panel which reads “out of service”. Hence, we wait, plan, and intensively manage our animals in order to properly cultivate this precious resource that the world has largely forgotten.

There are two ways to view our cattle grazing operation, both of which result in the same end. We either run a land management and carbon sequestration business in which nutrient dense, protein and fats are our byproducts, or we run a food production business which forbids itself from any crutches used to make food production mechanical and more linear, thus subjecting ourselves to the laws and natural orders of ecology which we must depend upon.

Regardless of which way we choose to view ourselves, our goals remain the same: in order to produce food of high quality, we must optimize photosynthesis on our fields. To properly manage land, we need animals who can harvest 100% of their own diet and convert it into walking biomass instead of letting those nutrients oxidize and end up back in the air, where the plants had previously pulled them out of.

Without falling into the ditch of simplifying biological processes by comparing them machines, I believe there is a helpful parallel to be made. Our cattle are the engines we run biomass through in order to be converted into meat, milk and calves. Different cattle throughout time have varied in efficiency converting grass into those things. To put it simply, not all cattle in this day and age can suddenly become fully grass-fed and not keel over, let alone produce quality beef.

The advent of cheap grain led to the justification of feeding it to livestock in large swaths. This choice threw out millennia of genetic selection that bred for cattle who were excellent converters of grass into protein and fat, to animals who could gain weight as rapidly as possible on the high octane fuel that is corn and soy. Most of the grass-finished beef on the market today takes this path; essentially formula one cars who are being fed diesel fuel.

There is a common concept amongst the grass-fed movement: the idea that consumers need to sacrifice taste and tenderness in order to claim that the beef they're eating is healthy, both ecologically and personally. To this sentiment I generally disagree. Although most grass-fed beef on the market is lean and tough, I don't think it has to be. Through our farm's careful selection of animals who have always run on the raw diesel that is an exclusive forage diet, we can obtain tenderness and fat on grass alone. The work of growing a herd that can efficiently convert precious forage into fat and protein is a lifelong endeavor; one that we hope to be able to pass along after we're gone.

For many of us, this is an entirely new way of viewing the world. We view resources as a gas tank that, if taken from too often, will be left desolate— which can be true of farming if done irresponsibly. However, in the abundance of creation, sometimes the opposite can be true. If we don’t take enough, there won’t be more. Organic grass-farming is more of a muscle in the sense that if our grass goes unused, we lose it. If we overuse it, we need to rest it and let it recover before using it again.

Resourcefulness seems more and more to be what the small farm lives and dies upon. We have these free gifts of soil, water and sunlight. How we then use these as they are allocated to us is what makes beef that tastes good, cows that milk well, and hogs whose flavor can’t be matched. In the “how” of accomplishing this we are either creating with and building upon what we’ve been given or we’re destroying it. There is no neutral way when it comes to grass; you’re either with it or against it.

This spring, we haven't mowed our lawn yet. It is an interesting psychological experiment-- letting a lawn become pasture. I can't help but step outside and wonder "What will the neighbors think?", but I remind myself that in a few weeks when they see our bull in the front lawn, maybe they too will yearn for the sound cattle munching outside of their homes. Perhaps, over time, the hum of lawn mowers every Saturday morning across the country may turn into the subtle sounds of food being grown. It's a silly dream I'd suppose, but isn't every dream that's one worth having a bit silly?

THANK YOU

We are filling up with June orders for our corn and soy free forested pork and our 100% grass fed beef, so don't hesitate to put your deposit down a head of time!

If you ever have any questions, want to chat, or are interested in seeing our operation firsthand, please don't hesitate to give us a call or drop us an email!

-Bennett and the Northaven Pastures Team

| Citations

Jenkins, Virginia Scott. The Lawn : A History of an American Obsession. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994. |