Your basket is empty

Already have an account? Log in to check out faster.

Already have an account? Log in to check out faster.

With a cigar in his mouth and a coffee in his hand, I spoke with fellow farmer this summer about, well, everything. As is common practice among many who live the life of solitude that farmers often do, there tends to be an “unloading” that happens when you catch one with some time to spare and something on his mind.

Among the topics discussed were the taxes he never can seem to pay enough of, the cost of fuel, and the trials of his current farming arrangement, but most interesting to me was the discussion of the 60 pounds he just lost.

“Someone told me I could go keto and just eat pork chops and drink cream all day. I thought to myself, I could do that!” he exclaimed, clearly feeling good in his lighter body. He then went on, “Now I understand why we’ve all been told that this stuff is bad for us for all these years… because they can’t feed the world on meat. That’s why they’ve convinced us not to eat it.”

I had never entertained this reasoning as to why the food pyramid was upside down. I had read about Ansel Keys’ research in the mid 1950s which popularized low fat diets, and which was ultimately funded by Crisco and the sugar industry. This research singlehandedly led to the government’s first issue of dietary guidelines. Yet despite the efforts to convince us otherwise, people weren’t dropping dead trying to figure out what to eat before tax dollars were used to start telling them (Teicholz, 2014).

This idea was new to me though— the notorious they had convinced us meat was bad for our health because there wasn’t enough to go around?

Good Housekeeping Magazine, 1962

It’s the way we love to think in the west. There’s only so many marbles, so just make sure you get yours! The world can only make x amount of food so if we all just eat our ration we can skate by. In this view, farms are just engines whose value and productivity are either stagnant or deprecative. It certainly is possible that the U.S. government’s dietary guidelines were influenced by the prospect of having to feed the world, and we know that the concept of feeding the world is the mantra of Bayer Monsanto and other large players in the industrial agriculture court for decades at this point. It’s how exposing the populous to a dose of carcinogens and immune-suppressing compounds on a daily basis all the while poisoning the waterways and rendering hundreds of species extinct every year is justified as collateral damage (Bassil, 2007 & Raven, 2021). This is all to perform the mandate that they have given themselves to “feed the world.”

But did the world ask them to feed it? And have they succeeded in doing so?

All it takes is waltzing into a big box grocery store to see the abundance of our era— more food than anyone could have imagined from any point in history other than our own. Food from all over the globe culminating in this one place: a market-on-steroids. No, better yet, a super-market. With places like these all over the country, the world must be fed at this point right? Unfortunately, not quite.

34 million people in the wealthiest country on Earth— yes, right here in the U.S.— go hungry every year. This includes nine million children. Globally, a staggering 828 million people have empty stomachs that often go days between meals, and if we factor in malnutrition 33% of people worldwide are severely deficient in key nutrients (Food Aid, 2023).

It probably doesn’t shock you to hear this. We all grew up hearing about those starving kids in Africa who somehow were helped by us finishing our plates at the dinner table. Yet when we consider the fact that these are real people, and a whole lot of them, these numbers should outrage us. We should be demanding more food production now to feed these people!

Was it always this way? After all, why are these populations starving all over the world? Especially considering the volume at which we are able to produce food so “cheaply.”

There is no simple or quick answer to these questions. Hunger has indeed always been an issue for all of human history. Drought, famines, wars, and blights have plagued food systems big and small since the dawn of time. The areas of the globe with the most civil unrest, terrorism and widespread violence are typically those who go hungry the most. I’d imagine its quite difficult to grow food in a war zone, let alone distribute it to others. However there is a variable here that is new and in our control: The simple laws of supply and demand at work has rendered these nations completely dependent on foreign aid.

According to World Vision, an organization which tracks the ongoing history of starving and malnourished countries in Africa, starvation and famine was not an issue in these places any more than many other semi-arid regions of the world until a drought began in the Sahel region of central Africa in 1968. This spanned for 12 years and led to roughly one million deaths (World Vision. 2022).

This in combination with several other smaller droughts and other sociopolitical elements throughout the next 30 years led to massive social unrest, migrations and, ultimately, destabilized nations. This qualified more developed regions to aid these nations to the best of their ability in order to keep the populous from starving further. I would say this was a righteous act, but what became of this situation was this: We never stopped sending aid. What started as a seemingly good thing meant was there was now a steady supply of free, low-quality food and clothing entering these region’s economies. Much like our nation’s welfare state, this created a system of dependence that disincentivized populations from creating their own sovereignty. After all, how can a local food producer’s prices compete with free?

Populations who were perfectly capable of thriving off of feeding themselves before these disasters struck have now built a culture and life around this incoming aid, which is also not always reliable. Sometimes the food truck won’t return back to these places for months at a time, and if this system were effective, why is there more hunger now than ever before? Malnutrition has risen exponentially since these regions have drifted from their local diet of a variety of crops and animal products to a diet made up of almost exclusively rice and wheat. This does not even supply them with nine essential amino acids, let alone the micronutrients and fats needed to have healthy brains and bodies.

African nations really did need help. They still do. We cannot create a culture and system of dependence and then just back out. Yet there is a better way— a way that doesn’t require the States to feed the world, because I personally believe that the world is perfectly capable of feeding itself. After all, if it wasn’t possible to produce food where these populations are, they wouldn’t be there in the first place.

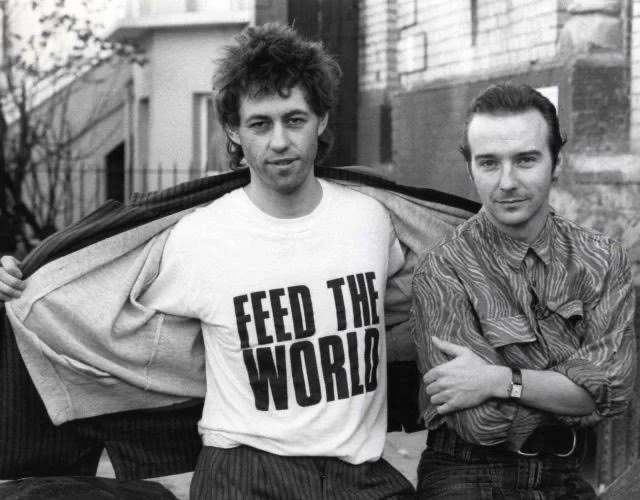

Bob Geldof and Midge Ura, writers of the iconic 1984 Christmas single, “Do They Know it’s Christmas?”

This is not a case to stop aiding the needy. So much of this world is currently war torn and women and children are suffering in droves because of the complex and corrupt places they have found themselves in. For many, the grain truck that comes to town every month is their only hope, but what if we thought bigger about people and smaller about food? What if, instead of assuming that the poor and needy of the world can’t survive without us, we see them for what they are: fearfully and wonderfully made people who are just as intelligent and capable as you and I and just need the right toolset. Or better yet, to give them back the toolset that was taken from them.

There are many who are already deep into solving these issues. Organizations such as Heifer International and the Savory Institute have been feeding communities in peril by giving livestock to them in mass. It is an incredibly simple and fruitful answer, which both organizations are seeing amazing results from. Land that has been cropped for decades (and is therefore extremely prone to drought) is being improved through controlled grazing. Local economies finally have a reason to improve and future to build.

One of the most exciting parts I find about this solution is that most of these developing nations still have the traditional wisdom to know how to herd, manage, and harvest the food from these dairy or meat herds. Thus, the education required is minimal to none.

This movement is contrasted with the other “teach-them-how-to-fish” nonprofits; the ones sponsored by Monsanto. The alternative movement is to move farming of GMOs and chemical input intensive farming to these countries. Several community action nonprofits funded by foundations such as the Gates and NIH are working rigorously to sell hungry nations their patented GMO seeds along with their petroleum based fertilizers and glyphosate. All of which are sold to them knowing that no one can afford the proper equipment to safely handle these toxic compounds and treated seeds. Vandana Shiva, an Indian Food Activist, points out in her book, Who Really Feeds the World, that this movement is not interested in feeding people at all, and certainly not long term (2016). They aren’t interested in creating producers, they’re there to create consumers of their products from whom they buy back their crops from for essentially below the costs of which they sold them. It’s a brilliant business model, but not a model that creates sovereign producers, nor one that has any interest in solving the malnourishment crisis. On the other hand, you can’t patent an animal or the native grasses that feed them. This may contribute to their lack of willingness to promote animal husbandry.

Livestock are a symbol of stability for any culture. Their need for daily care is a testament to the fact that tomorrow is hopeful enough to invest in the future today. Indeed, a herd of animals is a proclamation of hope. In ten years a cattle herd of three will create such abundance to become a herd of 60 cows producing progeny along with having already produced 60 animals to feed people. That’s 30 million calories produced in just the animals that were beefed, and another 30 million standing in the fields producing calves.

Grain is a crisis crop. It turns around quickly and it will fill you up, but that’s about it. When grain becomes the major or only food source for a population, it tells you a lot about the overall status of that culture and economy. The best and only way to feed the world well is if every community can feed itself. A globalized food system inherently brings injustice; a system can only reach certain scale before it begins to compromise the people who are the backbone of it. We want a system of producers, not consumers.

|

Farmers with their livestock in Mongu, Western Zambia |

| A Somali rancher herds cattle in Kismayo |  |

It’s fair to say that this topic was a bold undertaking for some guy with cows and pigs in upstate New York, and I might agree. Yet the overall purpose of this letter is not only to build culture around our farm and to keep our beloved supporters in the loop, but also to understand the why behind it all. I truly do believe that the model of agriculture we follow at Northaven is going to be the only way to feed people in 150 years— it’s the only way that makes sense to me. You might think that that’s nuts, and maybe I’m wrong. Perhaps my grandchildren will laugh at me for thinking this while they sip their cockroach tea and farm their GMO soy, but I don’t think thats the case. Our food may be niche or even “boutique” at the moment, but I couldn’t be less interested in producing boutique food. This is what normal food is, and I think what it will soon have to be considered so once again.

I’m no relativist— there is a right and wrong way to do things in this world. There is an imprint or whisper on how to properly steward creation everywhere you look outside of the confines of concrete, and perhaps we can ignore it for a few hundred years, but sooner or later the whispers become screams. Chronic disease, obesity and world hunger are all whispers of agony from the same issue, and it will get worse if we don’t start thinking small about our food. How much worse until those whispers become screams? What would it take? 100 million kids, 1 billion kids? Do we need to find out?

So where do we start? We start here. By saying that small farms can and must feed the world, we’re actually proclaiming something simple: People are capable of independence. We should love good ethical food because we love people.

If you ever have any questions, want to chat, or are interested in seeing our operation first hand, please don’t hesitate to give us a call or drop us an email!

Bennett & the Northaven Pastures team

|

Annotations: Bassil KL, Vakil C, Sanborn M, Cole DC, Kaur JS, Kerr KJ. Cancer health effects of pesticides: systematic review. Can Fam Physician. 2007 Oct;53(10):1704-11. PMID: 17934034; PMCID: PMC2231435. Food Aid. 2023. https://foodaidfoundation.org/world-hunger-statistics-2020/ Shiva, Vandana, 2016. Who Really Feeds The World? Teicholz, Nina. 2014. The Big Fat Surprise. World Vision. 2022. https://www.worldvision.org/hunger-news-stories/africa-hunger-famine-facts#:~:text=History%20of%20hunger%20and%20famine%20in%20Africa,-A%20look%20back&text=1968%20to%201980s%20%E2%80%94%20A%20drought,to%20widespread%20hunger%20in%20Uganda. |