Your basket is empty

Already have an account? Log in to check out faster.

Already have an account? Log in to check out faster.

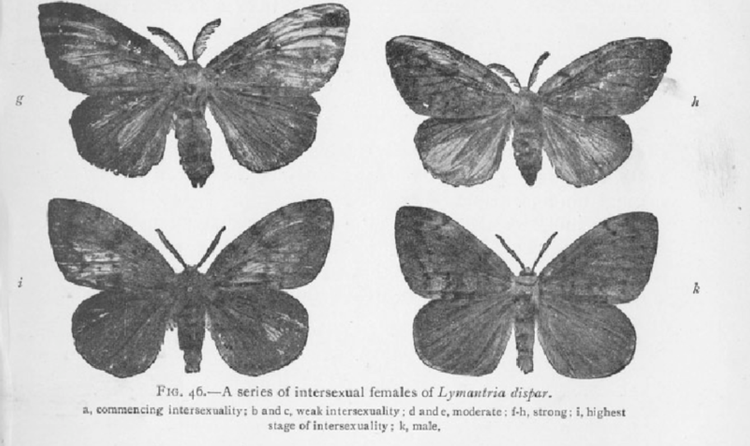

Welp, they have arrived. They have actually been here for a long time, but now, more than ever, you can see their presence. You may have noticed their impact if you spend anytime on the Taconic Parkway or simply hiking anywhere in the Hudson Valley. The “Gypsy Moth”, also known as the Spongy Moth, has plighted our forests and trees. The oak trees, above all other species in our woods, seem to be both the most desirable for these moths and the least able to handle them. So much so that when we walk through our predominate oak forest, it doesn’t feel much like a forest at all— it feels like we’re standing in a field with a bunch of logs popping out of the ground, the trees completely defoliated.

Although this invasive European moth was introduced to the Northeastern American ecosystem in 1864, our warm winters over these past two years have created ideal conditions for their proliferation, and the oaks are feeling it. They are impacted to the point that they may not come back from it. A tree can only go without photosynthesis for so long before it “starves”. Although this may feel catastrophic, and to a degree it is, it’s nothing new. Keep in mind that the woods we now look at and see an oak grove in once was a forest predominated by the Great American Chestnut, which once stood tallest amongst our woodlands and dominated over oak trees (with an estimated four billion mature trees standing). All this to say, our forests have gone through worse changes before.

|

Wood peckers and ant colonies have helped themselves to this compromised oak that has been killed after several years of being defoliated by the Spongy Moths. |

| Moth eggs— each sac containing up to 100 eggs to be hatched in only a matter of weeks. |

|

The American Chestnut used to be the keystone tree species in our region, its nuts feeding billions of critters and its wood a source of lumber that is unparalleled to this day in its hardiness and rot-resistance. We can vouch to this as our own 1850’s barn, being made of this invaluable lumber, still stands and doesn’t seem to be giving up anytime soon. What put an end to this great tree’s reign? According to The American Chestnut Foundation, the change occurred “at the turn of the 20th century with the introduction of a deadly blight from Asia. In about 50 years, the pathogen, Cryphonectria parasitica, reduced the American chestnut from its invaluable role to a tree that now grows mostly as an early-successional-stage shrub.”

I personally don’t think the Spongy Moth’s attack on our oaks is going to lead to the same sort of eradication. I have hope for our beloved oaks, but I do think there will be some growing pains and ecological changes to be made in the process. When confronted with pests and other big obstacles the farmer, or land steward, is left with two choices: Fight or Adapt.

Fighting, while important under many circumstances, I believe can often be a futile approach when it comes to these types of ecological whims. You will never win— at best you will keep problems at bay, and it is important to consider the cost of waging these wars. New York State has historically fought in dealing with the Gypsy Moth. Up until 2020, New York State sprayed aerial insecticide to keep these moths at bay, and it worked. They were not the problem they now are, but at what cost?

The organophosphates that were sprayed ubiquitously across our forests have been linked to multiple cancers and childhood neurodegenerative diseases. As Dr. Boyd Barr stated in a Cornucopia Institute article, “Upon entering the body—through ingestion, inhalation, or contact with skin—organophosphates inhibit cholinesterase, an enzyme in the human nervous system that breaks down acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that carries signals between nerves and muscles.” This is not to mention the impacts this has on our native pollinators and our ecosystem at large. Our state still sprays these insecticides on marshes and wetlands to keep mosquito hatchings down near the Bronx.

On our farm, we choose to adapt, which may be easier than we think in regards to an oak tree attack. Similar to poplar, willows and others, oaks have a unique ability to grow back after being harvested, a process known as coppicing. This is a potentially valuable tool under our belt as we consider how to foster an adaptive woodlot. We want our oaks. Not only for their majesty and environmental value, but also the agricultural value they add to our pigs, who are finished on the acorns they produce in the fall. However, it doesn’t look like our oaks will be giving us any acorns this year.

On our farm, we choose to adapt, which may be easier than we think in regards to an oak tree attack. Similar to poplar, willows and others, oaks have a unique ability to grow back after being harvested, a process known as coppicing. This is a potentially valuable tool under our belt as we consider how to foster an adaptive woodlot. We want our oaks. Not only for their majesty and environmental value, but also the agricultural value they add to our pigs, who are finished on the acorns they produce in the fall. However, it doesn’t look like our oaks will be giving us any acorns this year.

Our current plan is to coppice several oak trees and allow their regrowth by creating a young oak who now has the water inputs of an adult oak tree (through the stump it is growing out of). This young tree, through early exposure to these pests combined with ample nutrition for its small and low maintenance trunk, may be able to build immunity to these pests in a new way, that which they may carry with them into adulthood. Although cutting down our beautiful 80+ year old trees seems extreme, it may be our only choice, as they seem to be dying before our eyes due to the stress of the Spongy Moths eating away at their foliage for years straight.

This is us trying to create a robust forest that can survive this new ecosystem— one that has these pests in it. This is a general process that applies from animal husbandry to forestry to parenthood: Preparing the traveler for the road not the road for the traveler. We are striving to create trees who can do well in our ecology without any toxic inputs. This will be better for our forest in the long run.

This premise relates to how we raise animals organically. The conventional approach is to bolster up a herd of cattle with dewormers, vaccines, antibiotics and grain. Under these circumstances almost any animals can do well, but these are extremely fragile systems. Beyond the many downsides to the manure of these contaminated herds entering our ecosystems, what does consuming meat from animals who have had a lifetime of exposures to these products do? Maybe nothing, but maybe a lot. Additionally, all it takes is one new disease, one unpredictable event, and entire herds of livestock can be lost. Herds that are raised on these inputs are, by definition, unadaptable.

Instead we find animals who need nothing but grass, water, and salt to thrive; who gain weight properly on those elements alone; and who are resilient in new and unpredictable situations. This is why we have been so careful about the animals we purchase in building our cattle herd (and why we have such a long waitlist for our products). We are working hard to build a herd that will remain robust long after all of us are gone, no matter what our ever evolving world brings. Our new bull, Leroy, is a great example of this.

Welcome Leroy!

If you have been following us since the beginning, you will remember us discussing where we were purchasing animals from. On the top of that list was Harrier Field’s Farm, where the owners Mike and Joan have been carefully selecting the very best grass-fed Devon cattle for over 30 years. Leroy was brought to our farm in July to breed some of our cows, so that we may begin to incorporate Mike’s decades of hard work into our herd and continue his breed improvement program. Along with Leroy, four of Mike’s bred heifers will be joining us once they have been exposed to another one of his beautiful bulls on his farm.

Mike does not baby his cows, and neither do we. We want a herd that can thrive under higher pressure circumstances, such as disease and pests. A herd like this can only be cultivated through generations of intensive breed management, and all the hard work that Mike has put in which he is only beginning to see the fruit of. We will see more of it as we move through these next several decades, with hopes that our children will see benefits beyond what we knew was possible in our changing environment.

In the same vein, we hope that they can have a robust agri-forest with oaks hardier than any surrounding and cattle who can provide through thick and thin. Building these things will be a long and slow process for us, with many mistakes along the way. This is not the quick money type of wealth we have become addicted to since the 1950s— this is the slow, gradual building that will hopefully last long after all of our names are forgotten. Moths will come and go, new blights will enter and new challenges will always be on the horizon, but we have adaptation, holistic management and generational wisdom to always propel us forward.

If you ever have any questions, want to chat, or are interested in seeing our operation first hand, please don’t hesitate to give us a call or drop us an email!

Bennett & the Northaven Pastures team

|

References: American Chestnut Foundation (2023). Tree History Beyond Pesticides. (2022). Impacts on Wildlife. Doane, C. C, & McManus, M. L. (1981). The Gypsy moth:research toward integrated pest management. Herzl, Rina. (2020). Protect Honeybees and Pollinators by Ending the Use of Toxic Pesticides. Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility. New York City Department of Health. (2023). Health Department to Conduct First Ariel Larviciding of The Mosquito Season to Marshes and Other Nonresidential of The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island. Than, Ker. (2013). Organophosphates: A Common But Deadly Pesticide. |